By Clara Lehmann

“When we put on a mask, we think we’re hiding, but we’re really revealing.”

That is a quote from Michael Roh, an award-winning mathematics and physics teacher at University High School in Morgantown, WV. With an engineering degree from West Virginia University (WVU), Roh is not only an exceptional teacher, but he was awarded the Siemens National Teacher of the Year Award in 2005-2006. He is also secretly, or perhaps not so secretly, an artist. For nearly 25 years, Roh has created masks for an annual festival called Fasnacht, held in Helvetia, WV, a Swiss mountain village in Randolph County.

Helvetia’s Fasnacht, sometimes described as the Mardi Gras of Appalachia, is a Swiss celebration held near the end of winter. German for “fasting night,” Fasnacht is meant to serve as the grand hurrah before Catholics who are practicing Lent give up fatty foods and other physical comforts until Easter. According to Lee Palmer Wandel, author of “Voracious Idols & Violent Hands,” there is an essential interdependence between the excesses of Fasnacht and the austerity of Lent. Palmer Wandel writes, “The gluttony of the one and the emaciation of the other . . . are vital to Fasnacht’s identity.” She argues that without fasting, feasting would lose its definition. However, Helvetia’s Fasnacht has taken on its own Appalachian flair according to Roh. Instead of performing a religious rite, Helvetia celebrates the end of a harsh winter.

A Unique Celebration

To kick off this celebration, revelers from all over the state, country and even the world visit the rural community donning hand-made masks. Parading by candle-lit lampion, attendees walk from Helvetia’s Star Band Hall to the community hall. A familiar polka tune spills out of the warmly lit building as huge masks bobble through the narrow doorway. Upon entering, masked dancers are met by an effigy of Old Man Winter that hangs at the center of the dance floor. Dodging his rubber boots and the spruce twigs tucked into his sleeves, dancers enjoy waltzes, polkas, Swiss Schottisches and square dances as they work up an appetite for homemade doughnuts, rosettes and hozäblatz conveniently located near the band. Rosettes are a light and crispy deep-fried cookie prepared with a special flower-shaped iron. Hozäblatz, or pants patches, are paper-thin rectangles of dough pressed out on one’s knee, deep fried until crunchy and lightly dusted with sugar.

Photo courtesy of Dave Whipp

While some dance, others eat, and many partake in libations of the alcoholic variety outside the hall. At the stroke of midnight, an agile but sober local man or woman climbs on the shoulders of two strong—hopefully tall—men to cut Old Man Winter from his perch in the middle of the dance floor. Dragged to a bonfire outside, Old Man Winter meets his end to the sounds of cheering. This melding of the traditional pre-Lenten blow-out and a Druid winter festival makes Helvetia’s Fasnacht truly unique.

In fact, the Swiss who settled Helvetia in 1869 were mostly of Protestant faith, not Catholic, but the settlers held on to this festival from their motherland and continued to celebrate their version of Fasnacht well into the 1900s. Helvetia’s Fasnacht fell to the wayside during the 1950 McCarthy Era due to anti-German sentiments, but it was revived again in 1968 by Dolores Baggerly and Eleanor Fahrner Mailloux, two women who founded Helvetia’s acclaimed Swiss restaurant, The Hütte. In an interview from 2003, Mailloux explained that the very first Helvetia Fasnacht took place in one of the only Catholic households in Helvetia. “They sang and had a little celebration, so it must have been something that was very dear to them,” Mailloux lamented. She even described how masked children would go door-to-door asking for doughnuts and cookies much like Halloween.

Mailloux’s daughter, Heidi Mailloux Arnett, who has managed The Hütte since Mailloux’s death in 2011, expresses the importance of Fasnacht to the isolated community. “We’re given a license to indulge in excess at just the right time—a time when we’re all sick of winter,” she says.

Fasnacht, with all its vibrant colors, warm sounds and rich foods, arrives when the perils of a mountain winter get wearisome. “When Fasnacht arrives, we’re ready for some warmth and fun,” says local resident Jerianne Davis.

Rooted in Tradition

Mask-making became a theme of Helvetia’s Fasnacht after the event was revived in the late 1960s by Baggerly and Mailloux. Wishing to mimic the masked traditions of Switzerland’s Fasnacht in Basel, Baggerly and Mailloux encouraged participants to prepare their masks in secret. In fact, Mailloux often made her masks behind closed doors between preparing meals at The Hütte. After his first Fasnacht experience in 1992, Roh was inspired to try his hand at mask-making, too. He typically begins making a mask around Thanksgiving or Christmas. “Being a school teacher, I’m sort of relying on snow days to get my mask done,” says Roh. Without a distinct plan in mind, Roh finds inspiration all around him. “You see faces in a grain of wood, in crevices of a rock, even in a potato. We have an infatuation with faces.”

Photo courtesy of Dave Whipp

He is right. It is called pareidolia, a psychological phenomenon in which the mind perceives a familiar pattern where none exists. A common example is the man in the moon. Inspired by the faces all around him, Roh relies on these patterns and begins his mask by roughly molding chicken wire into a face. “Inner reflection comes out. It’s a bizarre thing,” he says.

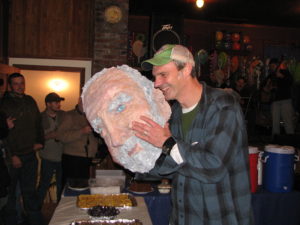

Roh describes the process of mask-making for Fasnacht as very meaningful, even venturing to call it cathartic. One of his favorite masks allowed him to grieve for his deceased friend, Rogers McAvoy. McAvoy, a WVU educational psychology professor, introduced Roh and his wife, Joni, to Fasnacht. After McAvoy’s death in 2011, Roh attempted to capture McAvoy’s face in a Fasnacht mask. “I started to make it and something was wrong,” says Roh. “I didn’t have him captured. I was mad, and I was thinking about just crushing it. That’s when I started to bend the wet papier-mâché. It was the craziest thing because it just became him. I could see the contours of his cheeks. Literally, I started bawling.”

One of the last things Roh does to finish his masks is figure out how he will see out of them. Not wishing to impact the connection his masks have with an audience, Roh tries to make the eye holes nearly invisible, which in turn means he will not be able to see well until removing the mask. “You’re in this shell,” Roh says of the unmasking tradition. “You can’t see that well, and you hear a muffled but familiar song as you make slow circles on the dance floor. It sounds like you’re in an aquarium. It’s beautiful. It’s one of the finest feelings.”

The truth of the matter is that Helvetia un-masks you. There is a giving in to the pace and the character of the small village that is required. Cell phones do not work, public Wi-Fi is rare, and life moves a little bit slower. One day each year in the dead of February, Helvetia invites you to celebrate Fasnacht, gives you glimpses into her history and identity and invites you to break your routine and perhaps a few societal rules. “Helvetia reminds you to give up trying to control your world,” says Roh.

On February 25, 2017 Roh will abide by the Fasnacht mantra of letting go, wear his 25th Fasnacht mask and reveal a little bit about himself. He, along with a few hundred others, will shuffle their feet to a folk tune and enjoy the sounds and tastes of Fasnacht in hopes for spring.

FASNACHT SCHEDULE:

Saturday, February 25, 2017

- 10 a.m. – 7 p.m. The Helvetia Mask Museum & General Store is open

- 11 a.m. – 8 p.m. Sampler plate at The Hütte Restaurant

- 3-8 p.m. Open Mic, food and beverages at the Star Band Hall

- 8:30-8:45 p.m. Lampion parade from the Star Band Hall to the Community Hall

- 8:45- 9 p.m. Mask judging and prizes awarded at the Community Hall

- 9 p.m. – 12 a.m. Masked ball at the Community Hall

- 12-1 a.m. Burning Old Man Winter outside the Community Hall

About the Author

About the Author

Clara Lehmann attended Carleton College in Northfield, MN. In 2010, she co-founded a post-production studio called Coat of Arms and serves as its producer and creative writer. Born in the Swiss-settled mountain village of Helvetia, WV, Lehmann grew up surrounded and inspired by the town’s beauty. Bridging a Southern charm with a ferocious determination, Lehmann balances her commercial work with documentary and narrative filmmaking. She wrote the award-winning documentary, “A Perfect Soldier” and co-directed, co-produced and wrote the short animated film entitled “Death Loves Life.” Lehmann has produced and written video content for clients like Google, Verizon, Jaguar, Land Rover, Marriott and The Onion.

1 Comment

Great article, had heard a little about the celebration, but never really understood what it was all about.