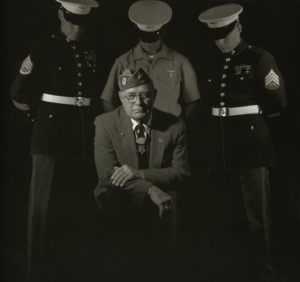

Hershel Woody Williams Medal of Honor Foundation

By Cathy Bonnstetter

Before Hershel “Woody” Williams became a Marine corporal and World War II veteran, a Medal of Honor recipient and veterans’ advocate, he was a taxi driver in Fairmont, WV, on the 6 p.m.-6 a.m. shift. He would sometimes also deliver Western Union telegrams to the families of fallen soldiers.

“The minute those families saw that envelope, they knew, and they would break down,” says Williams. “I was an 18-year-old boy. I didn’t know what to say or how to handle it.”

This tough-as-nails Marine carried those experiences in his soft heart through the decades, inspiring him as a soldier and driving his mission to recognize his fallen comrades through the Hershel Woody Williams Medal of Honor Foundation.

Inspired to Serve

When Williams was growing up in Quiet Dell, a small town in Harrison County, WV, his two older brothers were already serving in the U.S. Army. He had his eye on the Marine Corps, though, and dreamed of wearing its uniform.

“We had a couple Marines from the area, and when they came home, they were always in their dress blues,” he says. “They were required to wear them the entire time they were at home, and they looked sharp. These guys were neat and polite and could really take our girlfriends away from us.”

In November 1942, Williams, who had just turned 18, hurried down to the recruiter in Fairmont, WV, ready to sign up, serve his country and look sharp. He was met with great disappointment. The Corps had a height requirement of 5 feet 8 inches, and Williams stood 5 feet 6 inches. However, as the war effort grew, it took its toll on the Corps’ ranks. The Corps was eventually forced to change its height requirement, paving the way for Williams to achieve his dream.

Williams became a full-fledged Marine in May 1943, destined to serve in the Pacific theater. His first stop was Guadalcanal, a tropical island that was worlds away from the dairy farm where he grew up. It was there he learned to be a soldier.

“We trained with Marines who had already been through combat,” he says. “They trained us thoroughly on discipline and acceptance of orders. When they said that was your duty, you accepted it and went on to do it. I figured the more I learned, the better chance I had for survival.”

Williams was anxious going into battle, but he had a secret weapon to inspire his bravery. Her name was Ruby Dale Meredith.

“I never let myself think I wasn’t coming home to that beautiful lady I wanted to marry,” he says. “We became engaged before I left, and I would not permit myself to think I would not make it home to her.”

Courage at Iwo Jima

On February 23, 1945, when the flag went up on Iwo Jima, Williams and his fellow Marines felt their spirits lift, too.

“I had been there three days,” he says. “Some of the men had been there five days, and we had lost so many. The flag went up about 1,000 yards from where we were. When we saw Old Glory flying on that mountain, we began yelling and celebrating. We felt like we were going to win this thing.”

One thing stood between Williams’ company and victory: a line of pill boxes, bunkers made of a cement material that permitted the enemy to point their guns out a small opening in the front, wreaking havoc while remaining safe. Those cement bunkers were impenetrable.

Williams was asked to go in with a flame thrower, the only weapon that could be effective. He was given the order and told to choose four Marines to go with him to distract the enemy while he did his job. The mission took four hours.

“I have no explanation as to how I was able to eliminate seven of those pill boxes,” says Williams. “Of the four men with me, two gave their lives that day.”

Williams took some shrapnel in his leg on Iwo Jima and was tagged for evacuation, but he tore off the tag and stayed, serving in the Pacific until the atomic bomb ended the war.

A Hero Comes Home

October 5, 1945, President Harry Truman awarded Williams the Medal of Honor, the highest honor bestowed on military personnel and an honor that would later help him heal the emotional wounds he suffered during the war.

“I was ordered back to the States to receive the medal, and I decided after that I was going home to that beautiful lady I cherished,” says Williams. “When Harry Truman put that ribbon around my neck, it was still a bit of a mystery to me. I couldn’t figure out why I was selected for this honor.”

Although Williams came back to his girl a hero, he did not feel like a hero or even much like himself. He was torn between his mission and the realization that the enemies were young men like him.

“There was no PTSD at the time and nowhere to get help,” he says. “Your main source of comfort and adjustment was your family. I had taken too many lives in such a horrible way. I couldn’t forgive myself, but that was my order. My purpose was to win the war.”

Constantly being asked to talk about what led him to be a hero helped Williams find himself.

“I was forced to talk about my experience, and that was the best therapy I could have had,” he says. “I had a brother in the Battle of the Bulge who wouldn’t talk about it, and, consequently, it just ate at him.”

Eventually, in 1962, after wrestling with it for years, he decided to accompany his wife to church, and that helped him reconcile his mission with his heart.

“I always say I married a Methodist angel, and I ended up in church and realized I could get forgiveness and I could forgive myself,” he says. “I realized God was not holding me accountable.”

Honored for Service

In 1979, after 20 years in the Marine Corps and the Marine Corps Reserve and 33 years as a veterans’ service representative for the Department of Veterans Affairs, Williams retired. He then turned his attention to honoring vets by asking government officials to name bridges and highways after them so they would not be forgotten.

Throughout his life, he garnered a variety of honors stemming from his heroic service, and in Fairmont, WV, the National Guard Armory and the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 7048 were named in his honor. His Medal of Honor is the award he is most proud of—but not for the reasons anyone would expect.

“The medal was my biggest honor because of the other Marines who were willing to testify as to what happened that day,” he says. “To think they thought I was worthy to wear the nation’s highest honor is overwhelming. Even after 74 years it is still overwhelming. Why me? I don’t know the answer.”

On October 21, 2017, Williams was the recipient of another rare honor: the U.S. Navy christened the USNS Hershel “Woody” Williams, in San Diego, CA. Williams’ friend and fellow Marine, Ronald Wrobleski, was the one who sought to have the ship named in Williams’ honor.

“It used to be that you could not name a ship after a living person,” says Williams. “I told Ron I wasn’t ready to go yet, so it wouldn’t work out, but he wanted to try anyway. While he was getting endorsements, the Navy changed the rule.”

Wrobleski not only succeeded in getting a ship named after Williams, but he also succeeded in getting more than 70,000 endorsements for the name, setting a Navy record.

The ship, built by General Dynamics NASSCO, is the Navy’s newest Expeditionary Sea Base and was delivered to the Navy in February 2018. The 784-foot-long ship can host up to 250 personnel and has a 52,000-square-foot flight deck.

In addition to the ship’s name, the Navy had one more gift in store for Williams. Patrick O’Leary, veterans’ affairs manager for UPS Inc., revealed the names of the men who died defending Williams in Iwo Jima: Corporal Warren H. Bornholz and PFC Charles G. Fischer.

“I didn’t know those men’s names before then, but God knew. I wear the Medal of Honor in honor of their lives,” says Williams.

The Mission Continues

At 94, Williams still has the tenacity of that young Marine, and he travels the country giving speeches, participating in education events and furthering the mission of the Hershel Woody Williams Medal of Honor Foundation, which is dedicated to paying tribute to and supporting the families of fallen military personnel.

The foundation, established in 2010, put up its first memorial for Gold Star families—families who had loved ones killed in combat or other military activities—in Dunbar, WV. That monument became an internet sensation, prompting a national focus for the organization. The foundation has since dedicated monuments throughout the country, five of which are also in West Virginia. With approximately 60 projects currently underway, the foundation will have a footprint in about 40 states, and 30 states will host monuments. Williams is driven by the comfort he knows those monuments bring.

“I’ve had a number of people tell me, ‘Now I know my loved one will not be forgotten,’” he says.

Williams’ service to his country began with his fascination with a good-looking uniform, but it grew into a simple and eloquent sentiment he believes every American should remember.

“We are the most fortunate people in the world,” he says. “People serve in the military to keep us free.”

2 Comments

Woody is a great American, and a friend. His mission throughout his life has been to serve and protect others. I have seen him walk up to Naval Academy Cadets he didn’t know, and share a smile and thanks for their service.

Woody is a one-of-a-kind Humble Hero.

I have known Woody for decades and Honored to serve on his Founders Advisory Board of the Hershel W. “Woody” Williams Medal of Honor Foundation Honoring the Sacrifice of Gold Star Families. I would like to encourage everyone to visit http://www.hwwmohf.org and support this great cause.